Our memories of racing cars are usually of them in their element: in action, on a track, spitting fire, bumping doors and carving laps. But when race day is over, the cars are still here.

In period, they would be shipped or flown to the next race, or back to the factory shop. Once their usefulness is used up, however, they move on. It can be years before certain cars accrue the appreciation they deserve, as youngsters of those eras grow older and nostalgic.

Checking out some mean racing machinery at AWS Engineering. Can’t beat the Beemer… pic.twitter.com/LaWaKvMqgx

— Motoring Research (@Editorial_MR) December 5, 2018

These aren’t just ornaments, though. They’re used and raced, and thus need to be meticulously looked after. In industrial estates across the UK, businesses like AWS Engineering keep racing cars for storage, preparation and repair. Guys like these keep the racing cars you loved doing what they do best.

Alan Strachan started AWS Engineering back in 1996, with, among other things, a background of building and preparing Ford Mondeo touring cars. Who better to have look after your historic racer and, indeed, who better to give us a tour of the shop?

We start with a customer’s Group A Rover SD1 – one of the most successful Tom Walkinshaw Racing SD1s made. This car, Chassis 14, won the 1985 French Championship in Marlboro livery before moving on to the European Championship. It’s got the famous Tourist Trophy at Silverstone under its belt, too, as well as the Brands Hatch Grand Prix support race in 1986.

A similar Group A-spec car sits behind it, in green and blue British Leyland colours. It’s a tribute to chassis 010, which was ripped up in-period, and has been manufactured out of contemporary parts, including the original engine and suspension. Everything is exactly to Group A TWR spec.

While not an original car, it’s still worth over £115,000 to the right buyer who wants to go racing. A genuine winner can pull three to four times that amount.

- Take a tour of Prodrive’s collection of classic motorsport legends

“A lot of these cars are only as valuable as they are competitive,” explains Alan. “Not in the sense that they’ll win, but purely by having somewhere to race. This is a golden era in touring car racing, obviously, but there are also a lot of series and events – including Group A-specific stuff – where you can race them. It all contributes to why they’re so valuable. It’s the right time for them, too.”

Alan raises an interesting point. It seems logical that racing car values should be dictated by the amount of stuff owners can actually do with them and, moreover, how many others are getting involved.

The Ford Mondeo felt like the star of the facility. Perhaps by virtue of its being up on a ramp, like a plinth, or perhaps given it’s the car I personally most relate to. Perhaps it’s because it’s a super tourer, one of the coolest and most extreme breeds of touring car ever conceived. It also wears the iconic Valvoline livery, even though it isn’t one of the two most famous cars.

It’s the last Andy Rouse-built Mondeo from 1996 and was a machine that Alan himself worked on. In fact, this Mondeo was a prototype used to test smaller four-cylinder engines, before Ford moved its works team to West Surrey Racing and it reverted to V6 power.

Alan bought the car in 2014. It had previously been hill-climbing and racing throughout Europe. He returned it to British Touring Car Championship (BTCC) spec as a showcase, given latter-day super tourer racing was mooted to really take off not so long ago.

Alan reckons that hasn’t happened, partly because historic racers are mostly rear-wheel drive and these FWD ’90s cars simply can’t deliver the drifty drama. This, combined with the fact they’re costly to keep running, has somewhat neutered values. Alan clearly liked having a bit of his own history on the lot, though.

“Sentimentally, it’d be nice to keep it. It was bought with a view to take it out, show it and hopefully sell it. That’s why we dressed it in the most iconic Mondeo livery. I make no secret of it not being an original Valvoline car”.

It’s interesting that the Mondeo is worth £50,000 less than an SD1 with less provenance. “The marketplace for super tourers simply isn’t there, partly because the mainstay of historic motorsport is rear-wheel-drive cars. There was a championship and it was going quite well, but they changed the tyres and the grids dropped off. Whether that was an excuse I don’t know. We weren’t out with it this year because we were too busy.”

A Ford Sierra and the BMW 635 complete the Group A quartet. The 635 was BMW’s early Group A effort, with Schnitzer preparing cars for competition. This racing history is part of why the old 6er is such an iconic 1980s coupe today.

The BMW, which started life as a road car, was fitted with a Schnitzer-prepared six-pot motor, BMW Motorsport axles and a five-speed racing gearbox. It competed until 1988, before being tucked away for 20 years. It has even seen action on ice with studded tyres.

The Sierra is a bit more of a unicorn, given it’s an example of the car that pre-dated the Cosworth. The Merkur Cosworth was an American-spec car with a four-cylinder turbo engine (the same one that found its way into Foxbody Mustangs). This particular example is a recreation prepared by AWS, built from a Ford Motorsport shell – yours for £90,000.

It’s quite an interesting story of being the older, underdog sibling to the golden-child Cosworth. It proved the Sierra and four-pot turbo were a winning combo, with an XR4Ti Merkur winning the 1985 BTCC.

“I think the only reason the Merkur existed as a turbo car is that the Cosworth engine was already in the pipeline,” says Alan. “They wanted to do chassis development and see if a brawnier four-pot could have potential in the future. Without the Merkurs, the Cosworths could never have existed”.

It’s not just touring cars AWS looks after either. Among the super saloons, I spot an ex-Keke Rosberg Fittipadi F1 car from 1981, two Jaguar D-Types and a Taydek open-top sports car.

The Fiitipaldi is a 1981 F8/04, powered by the legendary Cosworth DFV 3.0-litre V8. It still sees action in the Masters Historic Racing series today.

The Jaguars are very different. It’s a testament to how incredibly alluring and valuable the D-Type is that a built-out-of-period replica could easily make £1 million. What about a real car? Well, it’s best not to speculate unless you’ve got at least £5,000,000 to play with.

The car in the shop is a 1955 original, sold new to the USA. It’s the 1956 Watkins Glen GP winner, no less. It’s also a proven winner in current historic racing, including victories at Silverstone Classic and Le Mans Classic.

The Taydek Mk3 is a curious little thing. Packing all of 1.8 litres, this car is straight out of the wedge era of sports car racing. This was a time when you could re-skin a Formula car with an open-air wedge and go racing at Le Mans, which this one did in 1971. It also won its class at the Reims 1,000km.

So that’s our tour of the cars in the shop, but it’s not the whole story. There were also a few other early-build cars in an incomplete state. These are cars that AWS are working on right now, with parts it can supply itself.

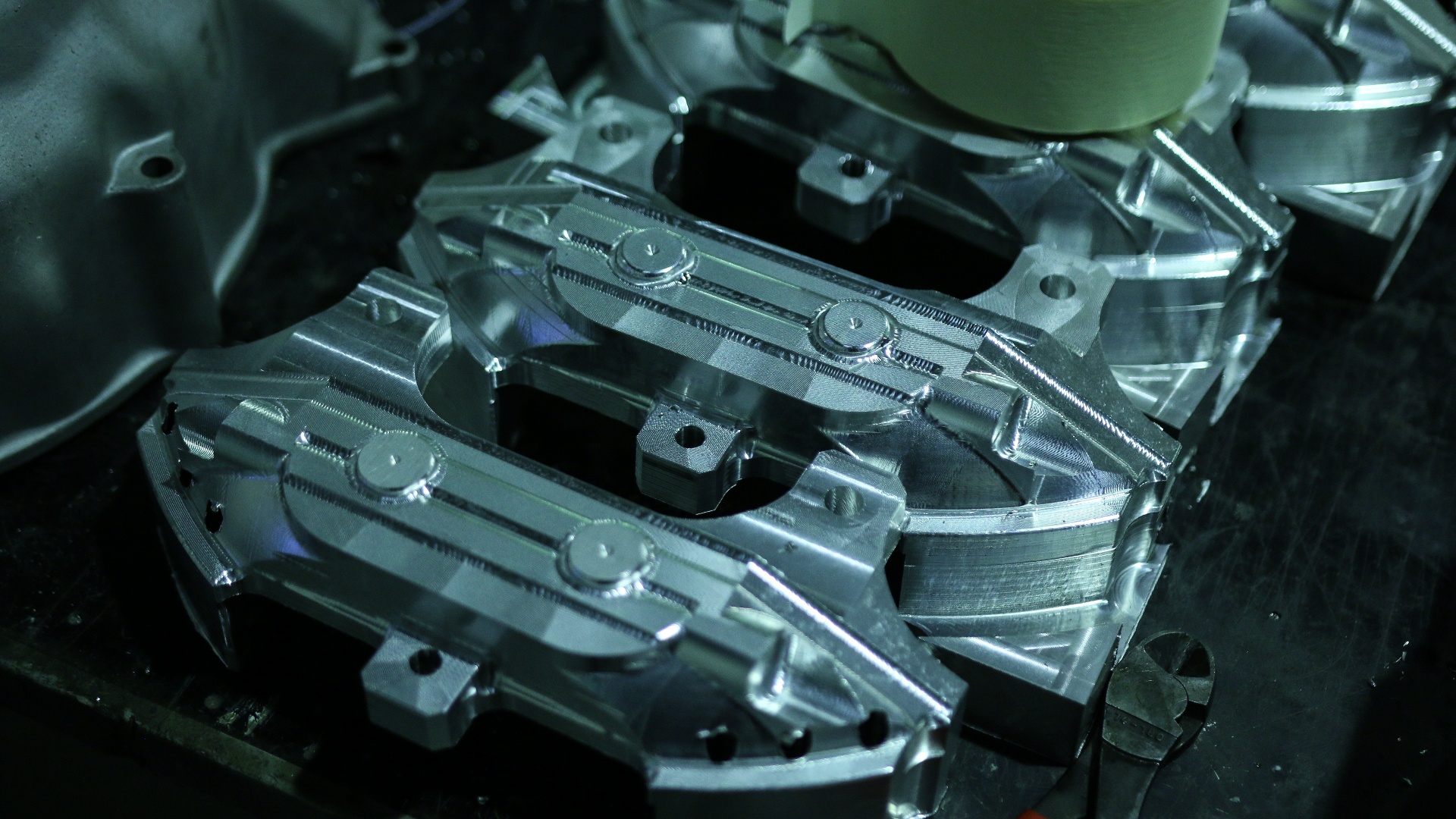

Tucked over in the corner of the unit are a selection of large milling machines. Their job is to cut all-new parts for classic racing cars out of billet materials.

Alan has experienced a life of looking after racing cars and, consequently, dealing with unreliable suppliers. His logic here is that if he’s the supplier, he has absolute control, and can be totally forthright with customers about when cars will be ready. It’s the logical next step for a restorer of old racing cars that use hard-to-find parts.

So, not only can AWS Engineering store, work on, fix, and prepare your car for racing, it can also make parts. The complete motorsport package, then? All you need is someone to race it. Our emails are open…

Read more:

- Lotus drifts into Christmas with tree-laden Evora 410

- Ferrari to celebrate Schumacher’s 50th birthday with special exhibition

- Cleaned-up Mini John Cooper Works returns