The Dodge La Femme arrived on the scene in 1955, a year when America was thriving with post-war prosperity. The baby boom was in full swing, and more people lived in the growing suburbs than in any other type of community, drawn by elbow room, fresh air, and affordable housing for growing families.

The Dodge La Femme arrived on the scene in 1955, a year when America was thriving with post-war prosperity. The baby boom was in full swing, and more people lived in the growing suburbs than in any other type of community, drawn by elbow room, fresh air, and affordable housing for growing families.

The rise of these new communities also gave rise to commuting; the vast majority of suburban families had at least one parent who drove to work. Groceries, household items, and sundries were generally not available at a convenient mom-and-pop corner store like in the city, but rather down the road at supermarkets and shopping centers with sprawling parking lots. A second family car was needed.

- The biggest and most flamboyant American cars

- 25 muscle cars that aren’t American

- We reunite Ford Lotus Cortina TV star with its owner after 40 years

Women were going to work in greater numbers than ever before by the mid-1950s, accounting for about one-third of the workforce and increasing overall household income. They were also taking a greater interest in cars; about one half of all adult women held a driver’s license. The automobile industry recognized that women were a growing presence in the marketplace, and actively sought to court to them.

Women were going to work in greater numbers than ever before by the mid-1950s, accounting for about one-third of the workforce and increasing overall household income. They were also taking a greater interest in cars; about one half of all adult women held a driver’s license. The automobile industry recognized that women were a growing presence in the marketplace, and actively sought to court to them.

In 1954, Nash was the first manufacturer to market a car specifically to women with the fresh, petite Metropolitan. That year saw the La Comtesse, the pink feminine half of “his and her” Chrysler show cars. General Motors also wanted a piece of the growing market, and design studio chief Harley Earl hired six women in 1955 to work across the various model lines in an effort to create cars that appealed to women. Those designers pioneered such modern automotive staples as retractable seat belts, child-proof doors, storage consoles, and vanity mirrors. One of those women, Sue Vanderbilt, overcame many obstacles to become a GM studio chief herself.

The birth of the Dodge La Femme

1955 also saw the unveiling of the Dodge La Femme, a trim package available for the Dodge Custom Royal Lancer. The car featured a pink-and-cream paint job and rose-printed upholstery, as well as a matching purse, umbrella, and other fashion accessories. It was marketed as being the first car for the modern American woman.

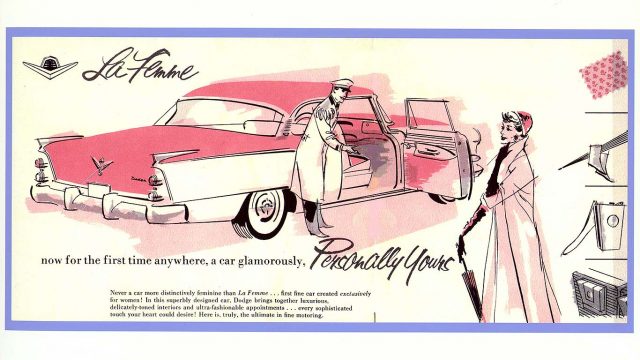

It can be hard to look back at a car like the La Femme. It is not an oddity; it represents the cultural values idealised by the media and advertising of its time. Today, offering a pink car with matching lipstick exclusively to women might be seen to be just as condescending as filling a car with potatoes and offering it to the Irish. Even in the period advertisement above, it’s not the driver’s door that is opened for her on what is said to be her own personal vehicle. Yet what the La Femme represents, however obtusely, is a recognition by the American automotive industry, and therefore the largest sector of industrial manufacturing on the planet, that women were an rising economic force, and that it was imperative that their specific wants and needs be addressed. So great was this tide that by 1958, GM executives from all over the country came to the unofficially named Feminine Auto Show to see the cars created by its six female designers. Not too many years later, Ford released its own car created to appeal to women: the now world-famous Mustang.

Yet what the La Femme represents, however obtusely, is a recognition by the American automotive industry, and therefore the largest sector of industrial manufacturing on the planet, that women were an rising economic force, and that it was imperative that their specific wants and needs be addressed. So great was this tide that by 1958, GM executives from all over the country came to the unofficially named Feminine Auto Show to see the cars created by its six female designers. Not too many years later, Ford released its own car created to appeal to women: the now world-famous Mustang.

Women now drive the automotive world. Women buy more than half of all new cars and influence up to eighty percent of car buying decisions. More women hold driver’s licenses than men. Women drive more miles and take more car trips than at any time in history, while the number of miles men drive has begun to decline. Car manufacturers now market their wares aggressively to women, and usually with dignity and respect. Yes, there are companies that take spectacular pratfalls and ignite social media firestorms, but overall the trend inspires pride in our societal accomplishments and hope for the future.

The La Femme can be viewed as a cynical design exercise, as Fifties kitsch, as social commentary, and many other things. The machine itself though, made of steel and fabric and devoid of the poisonous influences of humanity, is spectacular, in the strictest sense of the word.

Dodge La Femme: the legacy

Women make or influence a majority of new car purchases today, and manufacturers do everything they can to appeal to them. Marketing is a science, and demographics can target a person by age, gender, region, education level, and myriad more variables. Once a target demographic is acquired, the manufacturers do their best to present a vehicle that has the performance levels, economy, and features that demographic wants. This La Femme ad from 1956 illustrates the difference between a car “designed with the ladies in mind” (as stated in the above ad) and the modern practice of designing a car that offers the attributes a particular demographic wants.

Women make or influence a majority of new car purchases today, and manufacturers do everything they can to appeal to them. Marketing is a science, and demographics can target a person by age, gender, region, education level, and myriad more variables. Once a target demographic is acquired, the manufacturers do their best to present a vehicle that has the performance levels, economy, and features that demographic wants. This La Femme ad from 1956 illustrates the difference between a car “designed with the ladies in mind” (as stated in the above ad) and the modern practice of designing a car that offers the attributes a particular demographic wants.

The La Femme was discontinued after 1956. As it was a trim package and not a standalone model, production numbers are undocumented, but most agree about 2,500 were produced. Because it was only a trim package, it was not widely advertised, nor were demonstration models available at most dealerships. It’s demise is generally credited to lack of widespread public awareness of the product. Viewed through today’s standards, the marketing material shouts, “Hey, princess! Pink is for girls!” which hits every wrong nerve in modern psyches. It discolors perception of the La Femme, which is a powerful, well-engineered, and stylish vehicle. It’s designed by Exner, has a wicked Hemi under the hood, and comes with a matching umbrella, just like a new Rolls Royce.

Viewed through today’s standards, the marketing material shouts, “Hey, princess! Pink is for girls!” which hits every wrong nerve in modern psyches. It discolors perception of the La Femme, which is a powerful, well-engineered, and stylish vehicle. It’s designed by Exner, has a wicked Hemi under the hood, and comes with a matching umbrella, just like a new Rolls Royce.

Sadly, the Dodge La Femme may go down in history indistinguishable from the gibbering chauvinism that created it. Hopefully, we can learn to ignore its questionable parentage and let the La Femme be itself, standing proudly on its own four wheels.